Synchronization in a Distributed System

Most of us use distributed systems on a daily basis, and for good reason; the stability, fault tolerance and scalability they offer give us the flexibility to make more robust, high-performance applications. Distributed systems, however, come with their own set of unique challenges, including synchronizing data and making sense of conflicts.

Synchronizing data in a distributed system is an enormous challenge in and of itself. We often don’t know which version of a piece of data is the most up-to-date based on physical timestamp alone, as it’s nearly impossible to ensure that all entities (by which I mean processes or nodes from this point on) have perfectly synced physical clocks. Take, for example, two synchronized servers that write timestamps to the same system. If one server falls behind by even a few milliseconds, it would quickly be impossible to know the actual order of events. To solve this problem, we can use logical clocks based on events rather than time to build partially ordered sets.

You can almost think of logical clocks as a way to version the events in a system. By looking at these ordered sets, we can then synchronize our data across a system because we know, generally speaking, what pieces of data are the most up-to-date and are able to spot concurrent events.

I’ll admit that the first time I heard the terms “vector clock” or “Lamport timestamp”, I figured they were some insane mathematical algorithm that I’d never understand. Perhaps more importantly, I avoided learning about the subject altogether because of this fear. Fortunately, I discovered that their behavior is actually far simpler than I imagined. Let’s take a peek under the hood and find out how this all works.

Lamport Timestamps

Lamport timestamps, invented by Leslie Lamport in the late 1970s, are the simpler version of the two methods. Each entity in a system keeps its own counter that increments before each event it handles and includes this timestamp when it synchronizes with other entities. Again, keep in mind that these timestamps are not physical timestamps (i.e. today at 1PM), instead, think of them as numbers that only have meaning when compared to other timestamps within the same system.

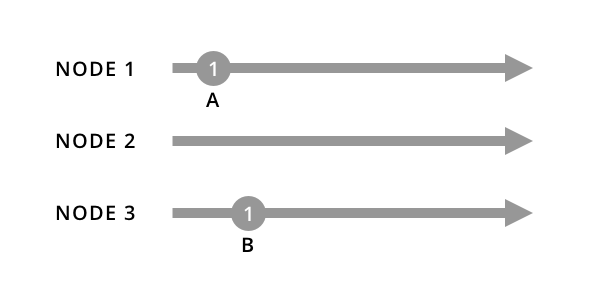

Let’s say we have a distributed system with three nodes and that they can each handle events independently of one another:

At this point, nodes 1 and 3 have handled events A and B, incrementing their respective Lamport timestamps to 1. But, they haven’t yet synchronized with node 2 or with each other, so let’s step ahead:

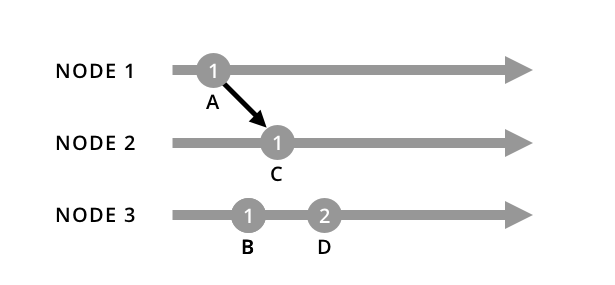

Now, nodes 1 and 2 have synchronized and node 1 sent along its timestamp, incrementing node 2’s timestamp to 1. We’ll step ahead once more:

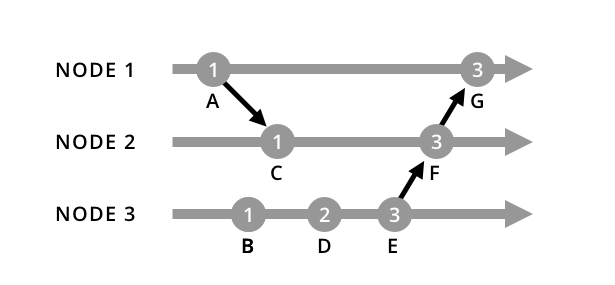

Node 3 has handled 2 events (D and E), and synchronized with the other two nodes. Notice that node 2’s Lamport timestamp increments to 3, skipping 2 because event E’s timestamp was already 3, a higher value.

Our nodes are now all synchronized, but what did our timestamp values really tell us? Lamport’s proof for this theorem is “surprisingly difficult,” so we won’t talk about the details of the algorithm here, but we know in the Lamport causal sense that event B came before D, E happened before F, and F happened before G.

Unfortunately, there are some things we don’t know since we’re not storing information about the state of the other nodes. For example, we have no way to tell if C happened before or after B or if they were concurrent. We would need to use vector clocks to meaningfully discern this information.

Vector Clocks

Independently developed by Colin Fidge and Friedemann Mattern in 1988, vector clocks give us greater context than Lamport timestamps and are used in systems like Riak. Instead of each entity storing only its own timestamp, it stores a vector of timestamps equal in size to the number of entities in the system. Each entity knows it’s own position in the vector, and the clocks of its sibling nodes when it last synchronized. You can almost think of it as a record of that entity’s knowledge of the rest of the system.

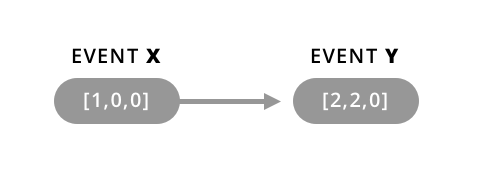

Remember that the synchronization events include the sender’s vector clock. By comparing these clocks, the algorithm can better determine the causal order of events. The comparison runs through each element in the vector clocks and then applies a few simple rules:

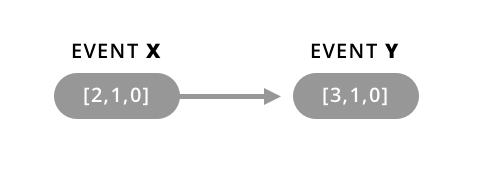

- If all of the timestamps for event X are less than or equal to all of event Y’s timestamps, then X came before Y and the events were not concurrent:

- If all of the timestamps for event X are greater than or equal to all of event Y’s, then Y came before X and the events were not concurrent:

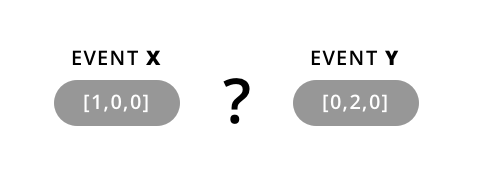

- If some of X’s timestamps come both before and after some of Y’s, however, then the writes are considered concurrent and we can’t discern the order:

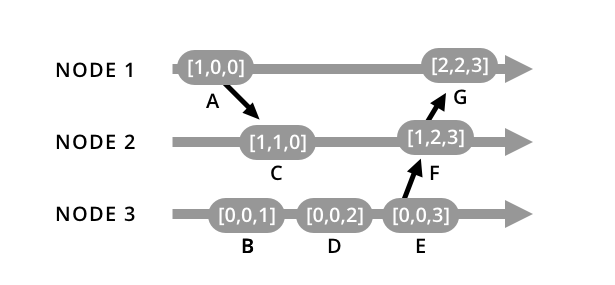

With these rules in mind, let’s take a look at the previous Lamport timestamp example, this time using vector clocks:

With Lamport timestamps, we weren’t sure if C happened before B, but given the last rule for vector clocks, we now know that they were actually concurrent events. This tells us that these events happened at about the same time.

Vector clocks aren’t without their limitations, however, as they can’t order all events since all we really have is a partial ordering–as evidenced by the previous example where we only know that events happened at about the same time. Truly concurrent writes, therefore, can be detected but not correctly ordered for this reason.

Conclusion

Hopefully you now have a better understanding of a few of the unique challenges inherent in synchronizing distributed systems and at least one approach to solving those challenges.

The more interesting takeaway here, however, is that with a little effort it’s possible to understand the “difficult” parts of the tools you use. Sure, you may never write your own vector clock system, but that’s not really the point. The kind of voluntary ignorance I had because I avoided the parts that were difficult to understand only served to undermine my growth as a craftsman. Dive in to the scary parts and I guarantee you’ll learn something.